Research through design as a method for interaction design research in HCI

1. p. 493

"Following a research through design approach, designers

produce novel integrations of HCI research in an attempt to

make the right thing: a product that transforms the world

from its current state to a preferred state."

2.

Christopher Frayling: research through design, 1993

3. What in RtD?

"What is unique to this approach to

interaction design research is that it stresses design artifacts

as outcomes that can transform the world from its current

state to a preferred state"

4. Why RtD?

"The artifacts produced in this type

of research become design exemplars, providing an

appropriate conduit for research findings to easily transfer

to the HCI research and practice communities."

5. How does RtD contribute?

"While we in no way intend for this to be the only type of research

contribution interaction designers can make, we view it as

an important contribution in that it allows designers to

employ their strongest skills in making a research

contribution and in that it fits well within the current

collaborative and interdisciplinary structure of HCI

research."

6. p. 495

"In adding to the research discussion of design methods,

Donald Schön introduced the idea of design as a reflective

practice where designers reflect back on the actions taken in

order to improve design methodology [22]. While this may

seem counter to the science of design, where the practice of

design is the focus of a scientific inquiry, several design

researchers have argued that reflective practice and a

science of design can co-exist in harmony"

7.

"...Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber proposed the concept of a

“Wicked Problem,” a problem that because of the

conflicting perspectives of the stakeholders cannot be

accurately modeled and cannot be addressed using the

reductionist approaches of science and engineering [21].

They argued that many problems can never be accurately

modeled, thus an engineering approach to addressing them

would fail."

8.

"Christopher Alexander’s work on Pattern Languages....

His work asks design researchers to

examine the context, system of forces, and solutions used to

address repeated design problems in order to extract a set

underlying “design patterns”, thereby producing a “pattern

language”...

The method

turns the work of many designers addressing the same

interaction problems into a discourse for the community,

allowing interaction designers to more clearly observe the

formation of conventions as the technology matures and is

reinterpreted by users."

9. p. 496

"Critical design presents a model of interaction/product

design making as a model of research [9]. Unlike design

practice, where the making focuses on making a

commercially successful product, design researchers

engaged in critical design create artifacts intended to be

carefully crafted questions. These artifacts stimulate

discourse around a topic by challenging the status quo and

by placing the design researcher in the role of a critic. The

Drift Table offers a well known example of critical design

in HCI, where the design of an interactive table that has no

intended task for users to perform raises the issue of the

community’s possibly too narrow focus on successful

completion of tasks as a core metric of evaluation and

product success"

http://designapproaches.wordpress.com/2012/03/22/bill-gaver/

10.

"Harold Nelson and

Erik Stolterman frame interaction design—and more

generally the practice of design—as a broad culture of

inquiry and action. They claim that rather than focusing on

problem solving to avoid undesirable states, designers work

to frame problems in terms of intentional actions that lead

to a desirable and appropriate state of reality."

11. p. 497

"It follows from Christopher Frayling’s

concept of conducting research through design where

design researchers focus on making the right thing; artifacts

intended to transform the world from the current state to a

preferred state."

12.

"Through an active process of ideating, iterating, and

critiquing potential solutions, design researchers continually

reframe the problem as they attempt to make the right

thing. The final output of this activity is a concrete problem

framing and articulation of the preferred state, and a series

of artifacts—models, prototypes, products, and

documentation of the design process."

reference: "epistemic artifacts"

13. p. 498

"Design artifacts are the currency of

design communication. In education they are the content

that teachers use to help design students understand what

design is and how the activity can be done."

14.

"These research artifacts provide

the catalyst and subject matter for discourse in the

community, with each new artifact continuing the

conversation."

"Christopher Alexander’s work on Pattern Languages....

His work asks design researchers to

examine the context, system of forces, and solutions used to

address repeated design problems in order to extract a set

underlying “design patterns”, thereby producing a “pattern

language”...

The method

turns the work of many designers addressing the same

interaction problems into a discourse for the community,

allowing interaction designers to more clearly observe the

formation of conventions as the technology matures and is

reinterpreted by users."

9. p. 496

"Critical design presents a model of interaction/product

design making as a model of research [9]. Unlike design

practice, where the making focuses on making a

commercially successful product, design researchers

engaged in critical design create artifacts intended to be

carefully crafted questions. These artifacts stimulate

discourse around a topic by challenging the status quo and

by placing the design researcher in the role of a critic. The

Drift Table offers a well known example of critical design

in HCI, where the design of an interactive table that has no

intended task for users to perform raises the issue of the

community’s possibly too narrow focus on successful

completion of tasks as a core metric of evaluation and

product success"

http://designapproaches.wordpress.com/2012/03/22/bill-gaver/

10.

"Harold Nelson and

Erik Stolterman frame interaction design—and more

generally the practice of design—as a broad culture of

inquiry and action. They claim that rather than focusing on

problem solving to avoid undesirable states, designers work

to frame problems in terms of intentional actions that lead

to a desirable and appropriate state of reality."

11. p. 497

"It follows from Christopher Frayling’s

concept of conducting research through design where

design researchers focus on making the right thing; artifacts

intended to transform the world from the current state to a

preferred state."

12.

"Through an active process of ideating, iterating, and

critiquing potential solutions, design researchers continually

reframe the problem as they attempt to make the right

thing. The final output of this activity is a concrete problem

framing and articulation of the preferred state, and a series

of artifacts—models, prototypes, products, and

documentation of the design process."

reference: "epistemic artifacts"

13. p. 498

"Design artifacts are the currency of

design communication. In education they are the content

that teachers use to help design students understand what

design is and how the activity can be done."

14.

"These research artifacts provide

the catalyst and subject matter for discourse in the

community, with each new artifact continuing the

conversation."

15. p. 499

"We differentiate research artifacts from design practice

artifacts in two important ways. First, the intent going into

the research is to produce knowledge for the research and

practice communities, not to make a commercially viable

product. To this end, we expect research projects that take

this research through design approach will ignore or deemphasize perspectives in framing the problem, such as the

detailed economics associated with manufacturability and

distribution, the integration of the product into a product

line, the effect of the product on a company’s identity, etc.

In this way design researchers focus on making the right

things, while design practitioners focus on making

commercially successful things."

"We differentiate research artifacts from design practice

artifacts in two important ways. First, the intent going into

the research is to produce knowledge for the research and

practice communities, not to make a commercially viable

product. To this end, we expect research projects that take

this research through design approach will ignore or deemphasize perspectives in framing the problem, such as the

detailed economics associated with manufacturability and

distribution, the integration of the product into a product

line, the effect of the product on a company’s identity, etc.

In this way design researchers focus on making the right

things, while design practitioners focus on making

commercially successful things."

16.

"research contributions should be artifacts that

demonstrate significant invention."

17.

CRITERIA FOR EVALUATING INTERACTION DESIGN

RESEARCH WITHIN HCI

(1) Process

- In documenting their contributions, interaction design researchers must provide enough detail that the process they employed can be reproduced.

- they must provide a rationale for their selection of the specific methods they employed.

(2) Invention

- Interaction design researchers must demonstrate that they have produced a novel integration of various subject matters to address a specific situation.

- In addition, in articulating the integration as invention, interaction designers must detail how advances in technology could result in a significant advancement.

- It is in the articulation of the invention that the detail about the technical opportunities is communicated to the engineers in the HCI research community, providing them with guidance on what to build.

(3) Relevance

- This constitutes a shift from what is true (the focus of behavioral scientists) to what is real (the focus of anthropologists).

- However, in addition to framing the work within the real world, interaction design researchers must also articulate the preferred state their design attempts to achieve and provide support for why the community should consider this state to be preferred.

(4) Extensibility

- Extensibility means that the design research has been described and documented in a way that the community can leverage the knowledge derived from the work.

EX 5. Short essay (400 words)

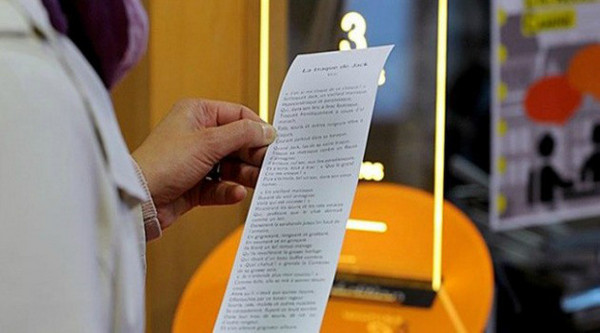

法國短篇小說販賣機

http://www.ettoday.net/dalemon/post/13022

http://short-edition.com/p/distributeurs-d-histoires-courtes

http://short-edition.com/p/distributeurs-d-histoires-courtes

1. critically review this artifact

2. discourse on the above project with 4 criteria of research-through-design approach.

(You may need to critically introduce this artifact and then discourse on four criteria in evaluation)

Deadline: 2016/4/12